Trainees’ intervention

Trainees' Intervention

1. Social Skills

Problem

- Children and adolescents with learning disabilities (LD) tend to face issues with social competence because it requires a large set of skills such as basic understanding of age-appropriate behaviour and social environments (Milligan, Phillip, & Morgan, 2015).

- Notably, they have difficulty in vocalising personal needs at the workplace, and often require assistance to guide them to express their needs (Ineson, 2015).

Solution - Smart Talk: A Social Skills Training Program

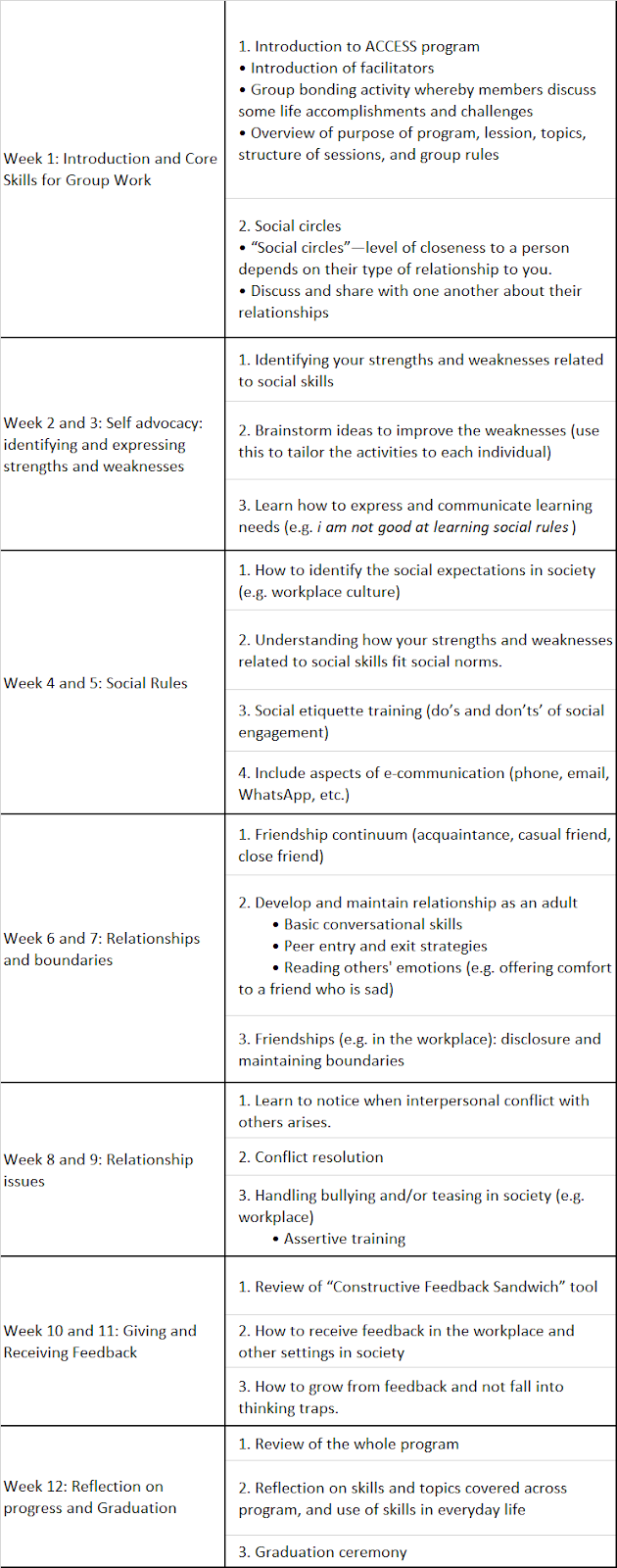

- Smart Talk is a hybrid program of the PEERS Program (Laugeson, Gantman, Kapp, Orenski, & Ellingsen, 2015) and the ACCESS Program (Oswald et al., 2018)

- This program will aim to improve social expression, social skills knowledge, social skills usage, and peer engagement in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

- Graduate and undergraduate students in psychology will be trained to conduct the activities, and supervised by a clinical psychologist

- The activities will be done in groups of 4 and each session will last for 80 minutes, with breaks in between.

- All participants will receive a program manual which outlines the activities, resources, and the reflection section

- The activity outline are as below:

- Across all activities, apply these strategies:

- Instructions should be presented via concrete rules and steps because adults with autism learn best via literal terms and enhanced abilities to remember facts (Gantman et al., 2012)

- E.g. "When you see a guest, must say hello and ask "how are you?" to the guest"

- Role-playing demonstration and practice (model social rules, initiate friendships, solve conflict etc.)

- Encourage perspective taking after the roleplay sessions

- E.g. "How do you think she felt when she was bullied?"

- Assign weekly homeworks for them to apply their learned skills outside of the program, and let both facilitators and parent/guardian to review them

- Organise a 10-minute practice session at the end of every session for them to practice their learned social skills

- E.g. Let the participants take 10 minutes to communicate among each other

- After every session, participants should reflect on what they learned and write them down in the provided program manual

- Parent/guardian responsibilities include:

- Review the homework assignment

- Refer to specific given instructions on the program manual on how to provide social coaching to young adults at home

- Continue the social coaching even after the program has ended

Evidence

Laugeson, Gantman, Kapp, Orenski, & Ellingsen, 2015 - PEERS Program

- Knowledge of social skills, social responsiveness, and frequency of social skills usage significantly improved from baseline to post-treatment

- Generally, participants that received the intervention had more significant improvements compared to the waitlisters.

Oswald et al., 2018 - ACCESS Program

- Social adaptive functioning was significantly higher after the treatment compared to baseline, and also compared to waitlisters

- Participants were more likely to seek social support from friends and family when facing difficulties after treatment, indicating improvement in expressing personal needs

2. Flexibility/adaptability

Problem

- Individuals with autism tend to perform more perseverative errors (repeating the same approach although it was wrong) compared to neurotypical people in adaptive tasks such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (Eylen et al., 2011)

- The WCST requires personal interpretation of their own errors to detect the switch (Eylen et al., 2011)

- People with autism may have deficits in their ability to monitor, interpret, and adjust their actions.

Solution - Play Activities

- 20 minute play activities that aims to improve cognitive flexibility, planning, and inhibitory control (Varanda & Fernandes, 2017).

Evidence (Varanda & Fernandes, 2017)

- Longitudinally designed study which lasted for three years; conducted among children with autism.

- After 21 weekly sessions, there was a significant reduction in the no. of perseverative errors and increment in perseverative responses (repetition of same response) after the activities and 1-year follow-up

3. Mood Regulation

Problem

- Among individuals with autism, studies have consistently found higher use of maladaptive emotion regulation (ER) methods than adaptive ER methods (Cai, Richdale, Uljarević, Dissanayake, & Samson, 2018).

- One possible reason would be that people with autism have limited abilities to identify and label their emotions.

Solution - Secret Agent Society

- Secret Agent Society: Operation Regulation intervention, originating from Australia, targets emotional awareness and regulation skills for children with ASD (Weiss et al., 2018)

- Facilitators are four graduate and one postdoctoral student, supervised by a clinical psychologist. Training included a 1-day seminar to familiarize them with the treatment manuals and various components of the intervention

- The activity outline is as below:

*Note: The exact instructions of each activity can only be found if we purchase the game/program package. We can choose to follow the exact activity gameplay/instructions or adapt the activities to suit the Malaysian context.

Evidence (Weiss et al., 2018)

- Improvements on internalizing (social withdrawal, depressed, etc.) and externalizing (aggression, hyperactive, etc.) symptoms and adaptive skills (daily living skills)

- Parents reported large reduction in children's emotional intensity and improvement in their ability to regulate emotions with social behaviour

- Overall gains were maintained even after intervention and during follow-up

(Thomson, Riosa, & Weiss, 2015)

- Overall, parents and children report an overall decrease in maladaptive emotion regulation methods and increase in using adaptive emotional regulation methods

4. Self-awareness

Problem

- People with Asperger's (AS), a milder form of autism, have lower levels of self-understanding than neurotypical people (Jackson, Skirrow, & Hare, 2012)

- They described less "me" characteristics (e.g. aspects of themselves) and "I" characteristics.

- They often identify themselves in simple descriptions.

- They view themselves in terms of permanent and unchanging self-characteristics (this may explain the need for "routines" to help them maintain their self-identity)

Solution - Photo Journaling

Note: This activity might be more effective/suitable for those with milder ASD symptoms or better expressive/communicative abilities

- Photo-journaling, adapted from photo-elicitation interview, a technique used to explore the self-understanding of people with ASD (King, Williams, & Gleeson, 2019)

- Use a camera to take photos of anything/anyone that represents who they are (minimum 10 photos)

- They will need to take photos based on existing themes, which includes but is not limited to these aspects of the ‘self’:

- E.g. hobby, favourite food/drink, loved ones, things that they are good/bad at, feelings, job, places they have been to, past memories. and future ambitions.

- The interviewer should preferably be someone with experience in qualitative interviewing, especially with individuals with autism

- About 2 weeks later, ask them to present those photos and explain what each photo and overall photo collection means to them. Use these interview questions to guide them :

- Is there any one photo that best represent you? Why?

- What do you like about this photo? Why?

- Why do you think you are good/bad at this? Why?

- Did you enjoy going to this place? Why?

- What is special about this memory? Why?

- *Note: feel free to ask other questions too (relevant questions based on their responses).

- Record their responses and assess whether they understand themselves better after doing this activity.

Evidence (King, Williams, & Gleeson, 2019)

- Through taking photographs and talking about them at interviews, all 10 adolescent participants with ASD were able to reflect upon who they are and what is important to them

- Most participants reported that they looked forward to seeing their photographs.

- Several participants commented that they would have found it more difficult to talk about themselves without the photographs.

5. Independent Travelling

Problem

- People with LD often have difficulty using public transport due to different sets of skills needed to do so such as memory, problem solving, and attention (Price, Marsh, & Fisher, 2017)

Solution - Google Maps

Note: the instructions may differ for each individual, depending on their baseline ability in using the app. E.g. those with higher ability/well-versed with the app may not need to use the cue cards. Or those with limited reading ability may need to use pictorial cue cards

- Google Map - help guide walking navigation and taking public transport (Yuan & Balint-Langel, 2019; Price, Marsh, & Fisher, 2017)

- Baseline (ability in using Google Maps): Provide instruction, “You are going to take the bus to _____” and then observe and document the number of steps that the participant completed independently. Once the participant indicated that they are unsure of the next step or made a mistake, the probe was terminated. The remaining steps were marked as incorrect

- Give them 6 cue cards with acronym: TRAVEL, serving as the 6 steps needed to plan their route on the app.

- T: Tap the app - locates and presses the Google Maps app

- R: Reach search bar - locates and presses the search bar in Google Maps

- A: Address - types the destination name in the search bar

- V: Validate address - confirms the address in one of two ways:

- Select the destination in the current city

- If there are two locations sharing the same name in the current city, ask for full address

- The student then clicks on the correct option in the dropdown list n the Google Maps

- E: Elect walking icon - presses the blue walking icon

- L: Load and route - click on the blue navigation icon on the route

- Teach them icons and symbols on the app (e.g. bus and walking icon)

- Learning how to use the app using constant time delay (CTD) instructions:

- 0 second delay task: guide them right after giving them instructions (e.g. point to letter T and read out the instructions, then model the steps)

- 5 second delay: If the participants performed the step independently within 5 seconds, we provide them praises or rewards. If they make mistakes or take longer than 5 seconds, guide them again. Once the participants performed the step independently for 5 consecutive trials, they have mastered the step and can proceed to the next step.

- The participant must also perform the mastered preceding steps while learning the new step (e.g. must complete step 1 again before learning step 2)

- When the participants performed all six steps independently, conclude the instructions

- Walking to the location

- Repeat all six steps again without instructions.

- Ask them to walk to the location following the app

- Follow the participants within a few feet behind while they walk to their destination. If they stop longer than 10 seconds or ask for help, provide an indirect verbal prompt

- Once they navigate to the location with/without assistance within 15 minutes, provide feedback, otherwise the probe will be terminated.

- Taking bus to the location

- Once they walk to the bus stop following the app, they will ride on the bus alone to te assigned destination and get off at the correct bus stop. The researcher will follow them behind in a car and meet them at the predetermined location. If the participant did not get off the bus at the correct bus stop, the researcher will alert them and discuss the mistake

- Maintenance session

- Assess whether they could still use the Google Maps app to travel to previously visited locations

- Extra sessions

- Additional session for those who struggle with specific steps. For each session, the participant was provided with 10 trials to describe how to use Google Maps to take the bus/walk to a specified location

Evidence

Yuan & Balint-Langel, 2019

- All three participants managed to complete all six steps on Google Maps to plan their route.

- Two participants successfully walked to the location without guidance, while only 1 participant required verbal prompts

Price, Marsh, & Fisher, 2017

- All four participants can complete all six steps on Google Maps to plan their route

- 3/4 participants were able to use Google Maps to take the bus independently (for both known and new locations)

- But, two of them sometimes missed a few steps, so they required extra sessions.

Trainees' Intervention

1. Social Skills

Problem

- Children and adolescents with learning disabilities (LD) tend to face issues with social competence because it requires a large set of skills such as basic understanding of age-appropriate behaviour and social environments (Milligan, Phillip, & Morgan, 2015).

- Notably, they have difficulty in vocalising personal needs at the workplace, and often require assistance to guide them to express their needs (Ineson, 2015).

Solution - Smart Talk: A Social Skills Training Program

- Smart Talk is a hybrid program of the PEERS Program (Laugeson, Gantman, Kapp, Orenski, & Ellingsen, 2015) and the ACCESS Program (Oswald et al., 2018)

- This program will aim to improve social expression, social skills knowledge, social skills usage, and peer engagement in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

- Graduate and undergraduate students in psychology will be trained to conduct the activities, and supervised by a clinical psychologist

- The activities will be done in groups of 4 and each session will last for 80 minutes, with breaks in between.

- All participants will receive a program manual which outlines the activities, resources, and the reflection section

- The activity outline are as below:

- Across all activities, apply these strategies:

- Instructions should be presented via concrete rules and steps because adults with autism learn best via literal terms and enhanced abilities to remember facts (Gantman et al., 2012)

- E.g. "When you see a guest, must say hello and ask "how are you?" to the guest"

- Role-playing demonstration and practice (model social rules, initiate friendships, solve conflict etc.)

- Encourage perspective taking after the roleplay sessions

- E.g. "How do you think she felt when she was bullied?"

- Assign weekly homeworks for them to apply their learned skills outside of the program, and let both facilitators and parent/guardian to review them

- Organise a 10-minute practice session at the end of every session for them to practice their learned social skills

- E.g. Let the participants take 10 minutes to communicate among each other

- After every session, participants should reflect on what they learned and write them down in the provided program manual

- Parent/guardian responsibilities include:

- Review the homework assignment

- Refer to specific given instructions on the program manual on how to provide social coaching to young adults at home

- Continue the social coaching even after the program has ended

Evidence

Laugeson, Gantman, Kapp, Orenski, & Ellingsen, 2015 - PEERS Program

- Knowledge of social skills, social responsiveness, and frequency of social skills usage significantly improved from baseline to post-treatment

- Generally, participants that received the intervention had more significant improvements compared to the waitlisters.

Oswald et al., 2018 - ACCESS Program

- Social adaptive functioning was significantly higher after the treatment compared to baseline, and also compared to waitlisters

- Participants were more likely to seek social support from friends and family when facing difficulties after treatment, indicating improvement in expressing personal needs

2. Flexibility/adaptability

Problem

- Individuals with autism tend to perform more perseverative errors (repeating the same approach although it was wrong) compared to neurotypical people in adaptive tasks such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (Eylen et al., 2011)

- The WCST requires personal interpretation of their own errors to detect the switch (Eylen et al., 2011)

- People with autism may have deficits in their ability to monitor, interpret, and adjust their actions.

Solution - Play Activities

- 20 minute play activities that aims to improve cognitive flexibility, planning, and inhibitory control (Varanda & Fernandes, 2017).

Evidence (Varanda & Fernandes, 2017)

- Longitudinally designed study which lasted for three years; conducted among children with autism.

- After 21 weekly sessions, there was a significant reduction in the no. of perseverative errors and increment in perseverative responses (repetition of same response) after the activities and 1-year follow-up

3. Mood Regulation

Problem

- Among individuals with autism, studies have consistently found higher use of maladaptive emotion regulation (ER) methods than adaptive ER methods (Cai, Richdale, Uljarević, Dissanayake, & Samson, 2018).

- One possible reason would be that people with autism have limited abilities to identify and label their emotions.

Solution - Secret Agent Society

- Secret Agent Society: Operation Regulation intervention, originating from Australia, targets emotional awareness and regulation skills for children with ASD (Weiss et al., 2018)

- Facilitators are four graduate and one postdoctoral student, supervised by a clinical psychologist. Training included a 1-day seminar to familiarize them with the treatment manuals and various components of the intervention

- The activity outline is as below:

*Note: The exact instructions of each activity can only be found if we purchase the game/program package. We can choose to follow the exact activity gameplay/instructions or adapt the activities to suit the Malaysian context.

Evidence (Weiss et al., 2018)

- Improvements on internalizing (social withdrawal, depressed, etc.) and externalizing (aggression, hyperactive, etc.) symptoms and adaptive skills (daily living skills)

- Parents reported large reduction in children's emotional intensity and improvement in their ability to regulate emotions with social behaviour

- Overall gains were maintained even after intervention and during follow-up

(Thomson, Riosa, & Weiss, 2015)

- Overall, parents and children report an overall decrease in maladaptive emotion regulation methods and increase in using adaptive emotional regulation methods

4. Self-awareness

Problem

- People with Asperger's (AS), a milder form of autism, have lower levels of self-understanding than neurotypical people (Jackson, Skirrow, & Hare, 2012)

- They described less "me" characteristics (e.g. aspects of themselves) and "I" characteristics.

- They often identify themselves in simple descriptions.

- They view themselves in terms of permanent and unchanging self-characteristics (this may explain the need for "routines" to help them maintain their self-identity)

Solution - Photo Journaling

Note: This activity might be more effective/suitable for those with milder ASD symptoms or better expressive/communicative abilities

- Photo-journaling, adapted from photo-elicitation interview, a technique used to explore the self-understanding of people with ASD (King, Williams, & Gleeson, 2019)

- Use a camera to take photos of anything/anyone that represents who they are (minimum 10 photos)

- They will need to take photos based on existing themes, which includes but is not limited to these aspects of the ‘self’:

- E.g. hobby, favourite food/drink, loved ones, things that they are good/bad at, feelings, job, places they have been to, past memories. and future ambitions.

- The interviewer should preferably be someone with experience in qualitative interviewing, especially with individuals with autism

- About 2 weeks later, ask them to present those photos and explain what each photo and overall photo collection means to them. Use these interview questions to guide them :

- Is there any one photo that best represent you? Why?

- What do you like about this photo? Why?

- Why do you think you are good/bad at this? Why?

- Did you enjoy going to this place? Why?

- What is special about this memory? Why?

- *Note: feel free to ask other questions too (relevant questions based on their responses).

- Record their responses and assess whether they understand themselves better after doing this activity.

Evidence (King, Williams, & Gleeson, 2019)

- Through taking photographs and talking about them at interviews, all 10 adolescent participants with ASD were able to reflect upon who they are and what is important to them

- Most participants reported that they looked forward to seeing their photographs.

- Several participants commented that they would have found it more difficult to talk about themselves without the photographs.

5. Independent Travelling

Problem

- People with LD often have difficulty using public transport due to different sets of skills needed to do so such as memory, problem solving, and attention (Price, Marsh, & Fisher, 2017)

Solution - Google Maps

Note: the instructions may differ for each individual, depending on their baseline ability in using the app. E.g. those with higher ability/well-versed with the app may not need to use the cue cards. Or those with limited reading ability may need to use pictorial cue cards

- Google Map - help guide walking navigation and taking public transport (Yuan & Balint-Langel, 2019; Price, Marsh, & Fisher, 2017)

- Baseline (ability in using Google Maps): Provide instruction, “You are going to take the bus to _____” and then observe and document the number of steps that the participant completed independently. Once the participant indicated that they are unsure of the next step or made a mistake, the probe was terminated. The remaining steps were marked as incorrect

- Give them 6 cue cards with acronym: TRAVEL, serving as the 6 steps needed to plan their route on the app.

- T: Tap the app - locates and presses the Google Maps app

- R: Reach search bar - locates and presses the search bar in Google Maps

- A: Address - types the destination name in the search bar

- V: Validate address - confirms the address in one of two ways:

- Select the destination in the current city

- If there are two locations sharing the same name in the current city, ask for full address

- The student then clicks on the correct option in the dropdown list n the Google Maps

- E: Elect walking icon - presses the blue walking icon

- L: Load and route - click on the blue navigation icon on the route

- Teach them icons and symbols on the app (e.g. bus and walking icon)

- Learning how to use the app using constant time delay (CTD) instructions:

- 0 second delay task: guide them right after giving them instructions (e.g. point to letter T and read out the instructions, then model the steps)

- 5 second delay: If the participants performed the step independently within 5 seconds, we provide them praises or rewards. If they make mistakes or take longer than 5 seconds, guide them again. Once the participants performed the step independently for 5 consecutive trials, they have mastered the step and can proceed to the next step.

- The participant must also perform the mastered preceding steps while learning the new step (e.g. must complete step 1 again before learning step 2)

- When the participants performed all six steps independently, conclude the instructions

- Walking to the location

- Repeat all six steps again without instructions.

- Ask them to walk to the location following the app

- Follow the participants within a few feet behind while they walk to their destination. If they stop longer than 10 seconds or ask for help, provide an indirect verbal prompt

- Once they navigate to the location with/without assistance within 15 minutes, provide feedback, otherwise the probe will be terminated.

- Taking bus to the location

- Once they walk to the bus stop following the app, they will ride on the bus alone to te assigned destination and get off at the correct bus stop. The researcher will follow them behind in a car and meet them at the predetermined location. If the participant did not get off the bus at the correct bus stop, the researcher will alert them and discuss the mistake

- Maintenance session

- Assess whether they could still use the Google Maps app to travel to previously visited locations

- Extra sessions

- Additional session for those who struggle with specific steps. For each session, the participant was provided with 10 trials to describe how to use Google Maps to take the bus/walk to a specified location

Evidence

Yuan & Balint-Langel, 2019

- All three participants managed to complete all six steps on Google Maps to plan their route.

- Two participants successfully walked to the location without guidance, while only 1 participant required verbal prompts

Price, Marsh, & Fisher, 2017

- All four participants can complete all six steps on Google Maps to plan their route

- 3/4 participants were able to use Google Maps to take the bus independently (for both known and new locations)

- But, two of them sometimes missed a few steps, so they required extra sessions.

Comments

Post a Comment